Greetings from Kakunen (Mr. K.) now Training at Jyomanji

Collapse

This topic is closed.

X

X

-

Mp

Mp -

Kakunen

Kakunen

OK.But please teach me detail.

I will come back Sodo,I will have Zazenkai.So I wanna try lots of way.

Sent from my iPhone using TapatalkComment

-

Mp

Mp

Comment

-

Kakunen

Kakunen

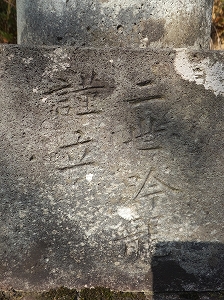

There is this temple.Hi K,

You mean that his Soto temple was, centuries ago, a Shingon Buddhist temple? That is actually very common as temples converted a long time ago. (Shingon Buddhism is old school of esoteric Buddhism in Japan)

Or, do you mean that Rev. Sasagawa is both Soto priest and Shingon priest? I don't think you mean that, because it is not common at all.

Gassho, J

SatToday

Comment

Mr. K,

Sodo comes first. We always sit together in timeless space no matter what <smile> Deep bows for your training, and do not worry. We support you fully.

Gassho

Kim

Sat today

Sent from my SM-G900P using Tapatalk鏡道 | Kyodo (Meian) | "Mirror of the Way"

visiting Unsui

Nothing I say is a teaching, it's just my own opinion.Comment

Kakunen

Kakunen

Greetings from Kakunen (Mr. K.) now Training at Jyomanji

I want to especially read and hear English well.

Now this is my theme.If you have some idea ,please teach me.

Today we discuss in member of our temple.

Now in Japan,Zen is just Losing substance.

People at oversea is more serious attitude for Zen.

And in Japan kind of taboo using internet for Zen.

Here in Tenryuji monk Seigaku who live in Berlin is managed of International connection.But he is busy.

I hope our connection will be good and hope people helped by Zazen.

Seigaku is young.And also friend of monk Koya at Jyomanji.

We need young power.But too young people is difficult to understand deeply about Zen.

Sent from my iPhone using TapatalkComment

Kakunen

Kakunen

For all

I will go to Zuioji at 4th of May.

I send again later.Today is work day!

Sent from my iPhone using TapatalkComment

Koun Franz's account of Tangaryo at Zuioji, the days kept sitting Zazen in waiting before formal admittance .... Tangaryo means almost literally "The Overnight Waiting Room".

================

I entered Zuiouji on March 1, and though it had been cold in the days previous, March 1 was a sunny, beautiful day, so I didn’t wear any long underwear or think in terms of keeping warm. After standing outside the gates and finally being granted provisional entry, I was placed with one other monk in tangaryō, a corner room with thin walls and window frames that didn’t quite fit the windows. We were told to sit in zazen all day, and so we did.

We knew this was to last a week, but we were constantly threatened with more. Inspecting monks would burst in at odd hours to see if we were really sitting or not. We were told that if we couldn’t use our bowls skillfully by the end of the week, we would be a burden on the group, and would have to stay one more week in seclusion for good measure. We were constantly encouraged to go home, told that we really were not monk material.

The first night, I went to sleep tired but full of resolve. The second day, it snowed hard, and the snow came into the room through those ill-fitting window frames and gathered on my lap. Thus began a week of being so cold that I couldn’t stop shaking, ever. At night, in bed, I shivered so hard that my jaw ached, and I often felt I couldn’t breathe. And of course, doing zazen literally all day every day, my legs felt as if they’d been hit with hammers. I would lie in bed, moving between two thoughts: first, that I had chosen this, and second, that I did not know why. I tried every kind of pep talk, every kind of mental game imaginable to somehow escape that physical reality, or to feel better, or to feel stronger. I felt I had been reduced to nothing, in a matter of days.

But around the fifth day, I gave up. I gave up trying to make it better. And I gave up hope that it would get better with time. I had settled into a very cool place, as if sitting still in the most remote chamber of a deep, deep cave. I did not feel warm—I was still freezing. My legs still ached so badly that it was difficult to walk to the bathroom and back. I had chillblains on my ears—they looked, and felt, as if they were made of bloody crepe paper. I had let go of my fantasies about how wonderful this would all be, how spiritual. I no longer imagined that I would be transformed here into a certain kind of person, or that I would learn things that no one else knows. I could see in the monks who visited us that while some were quite kind in their strictness, all were human, and some were simply children, enjoying power over someone of lesser rank. Even in seclusion, I could see clearly that this monastery would not transform us all into walking embodiments of compassion. Until that day, I could not have known how much baggage I had carried with me into that monastery.

So I gave up. But I did not quit. I did not do what a rational person might do, which is to pack up my things, politely thank everyone for the food and shelter, and go home. I cannot say why I didn’t leave—I’m certain that at times in my life, I would have. But I stayed. It may seem too simple, but now, years later, much of my understanding of Zen practice comes down to just this: to give up, then to continue anyway.

When I first started reading about Zen, I was struck by the depictions of Zen masters as spontaneous, unconstrained beings. The word “spontaneous” came up a lot, actually. They did and said thing…

When I first started reading about Zen, I was struck by the depictions of Zen masters as spontaneous, unconstrained beings. The word “spontaneous” came up a lot, actually. They did and said thing…

Last edited by Jundo; 04-29-2017, 06:09 AM.ALL OF LIFE IS OUR TEMPLE

Last edited by Jundo; 04-29-2017, 06:09 AM.ALL OF LIFE IS OUR TEMPLEComment

Mp

Mp

Comment

Deep bows, so much respect for your journey. I continue to sit for you. Thank you for sharing your practice with us.

Gassho

Kim

Sat today

Sent from my SM-G900P using Tapatalk鏡道 | Kyodo (Meian) | "Mirror of the Way"

visiting Unsui

Nothing I say is a teaching, it's just my own opinion.Comment

Kakunen

Kakunen

Maybe this story is hard for begginer.

I sit Sesshin at Antaiji 15hour at day.And I used Oryoki-bowl everyday.

And in Tenryu-ji sitting under snowing.

I will be cool attitude.Comment

Kakunen

Kakunen

Greetings from Kakunen (Mr. K.) now Training at Jyomanji

Maybe this story is hard for begginer.Koun Franz's account of Tangaryo at Zuioji, the days kept sitting Zazen in waiting before formal admittance .... Tangaryo means almost literally "The Overnight Waiting Room".

================

I entered Zuiouji on March 1, and though it had been cold in the days previous, March 1 was a sunny, beautiful day, so I didn’t wear any long underwear or think in terms of keeping warm. After standing outside the gates and finally being granted provisional entry, I was placed with one other monk in tangaryō, a corner room with thin walls and window frames that didn’t quite fit the windows. We were told to sit in zazen all day, and so we did.

We knew this was to last a week, but we were constantly threatened with more. Inspecting monks would burst in at odd hours to see if we were really sitting or not. We were told that if we couldn’t use our bowls skillfully by the end of the week, we would be a burden on the group, and would have to stay one more week in seclusion for good measure. We were constantly encouraged to go home, told that we really were not monk material.

The first night, I went to sleep tired but full of resolve. The second day, it snowed hard, and the snow came into the room through those ill-fitting window frames and gathered on my lap. Thus began a week of being so cold that I couldn’t stop shaking, ever. At night, in bed, I shivered so hard that my jaw ached, and I often felt I couldn’t breathe. And of course, doing zazen literally all day every day, my legs felt as if they’d been hit with hammers. I would lie in bed, moving between two thoughts: first, that I had chosen this, and second, that I did not know why. I tried every kind of pep talk, every kind of mental game imaginable to somehow escape that physical reality, or to feel better, or to feel stronger. I felt I had been reduced to nothing, in a matter of days.

But around the fifth day, I gave up. I gave up trying to make it better. And I gave up hope that it would get better with time. I had settled into a very cool place, as if sitting still in the most remote chamber of a deep, deep cave. I did not feel warm—I was still freezing. My legs still ached so badly that it was difficult to walk to the bathroom and back. I had chillblains on my ears—they looked, and felt, as if they were made of bloody crepe paper. I had let go of my fantasies about how wonderful this would all be, how spiritual. I no longer imagined that I would be transformed here into a certain kind of person, or that I would learn things that no one else knows. I could see in the monks who visited us that while some were quite kind in their strictness, all were human, and some were simply children, enjoying power over someone of lesser rank. Even in seclusion, I could see clearly that this monastery would not transform us all into walking embodiments of compassion. Until that day, I could not have known how much baggage I had carried with me into that monastery.

So I gave up. But I did not quit. I did not do what a rational person might do, which is to pack up my things, politely thank everyone for the food and shelter, and go home. I cannot say why I didn’t leave—I’m certain that at times in my life, I would have. But I stayed. It may seem too simple, but now, years later, much of my understanding of Zen practice comes down to just this: to give up, then to continue anyway.

When I first started reading about Zen, I was struck by the depictions of Zen masters as spontaneous, unconstrained beings. The word “spontaneous” came up a lot, actually. They did and said thing…

When I first started reading about Zen, I was struck by the depictions of Zen masters as spontaneous, unconstrained beings. The word “spontaneous” came up a lot, actually. They did and said thing…

I sit Sesshin at Antaiji 15hour at day.And I used Oryoki-bowl everyday.

And in Tenryu-ji sitting under snowing.

I will be cool attitude.I do my best

I do not say this is easy,but this is not hard.Last edited by Guest; 04-30-2017, 01:03 PM.Comment

Kakunen

Kakunen

Copyright © 2024 Treeleaf Zendo

Powered by vBulletin® Version 6.0.4

Copyright © 2024 MH Sub I, LLC dba vBulletin. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2024 MH Sub I, LLC dba vBulletin. All rights reserved.

All times are GMT. This page was generated at 01:34 AM.

Working...

Comment