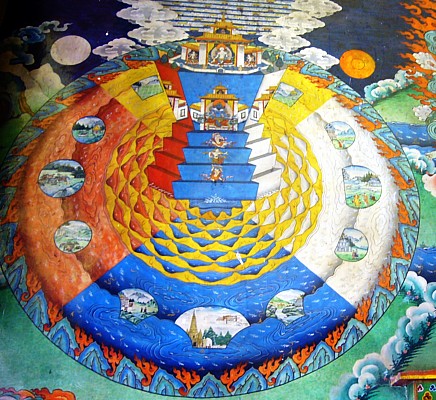

Dear Fellow Inhabitants of Jambudvipa **

**(the continent of traditional Buddhist geography where humans live, blue in the image above, layered heavens rising over ... ),

We may not turn turn this world into some perfect place, not soon (I think never). I am no utopian, offering visions of ideal heavens on earth, each and all of our societal and personal problems cured once and for all, not to return. In fact, I believe that life needs to remain wild, organic, unpredictable and sometimes harsh for life to be life. The rough and tumble world of "Saṃsāra," birth and death (with sickness, aging and other troubles in between), will always be quite saṃsāric.

On the other hand, I do believe that just a few relatively minor "tweaks" in human nature would render Saṃsāra, if not an utopian ideal, then quite nice and better. Small changes in our worst human habits would resolve a slew of planetary problems that now plague us. Moderating the tendency among some small number of us to kill and maim because anger boils over to rage, increasing feelings of human empathy when witnessing the fears, physical and economic suffering of others (even distant others), lessening our insatiable desires to consume and hoard in excess (notice that 'in excess' is always the problem for the Buddhist) would reduce or eliminate a variety of harms tied to those tendencies, from violence in our families and city streets, to most war, to hunger and poverty, to excess consumption of resources, global warming and more.

In the following I continue to ask, assuming that certain medical, genetic and other technological developments ...

(1) are inevitable and coming anyway, cannot be halted, cannot be ignored;

(2) have a high chance of being misused by bad actors unless we use them in beneficial ways;

(3) can be shown to be effective and safe to use; and

(4) can be introduced in an ethical way respectful of individual free choice, civil and human rights ...

(2) have a high chance of being misused by bad actors unless we use them in beneficial ways;

(3) can be shown to be effective and safe to use; and

(4) can be introduced in an ethical way respectful of individual free choice, civil and human rights ...

... how should such technologies be best employed to heal some of what troubles this world??

My book states:

~ ~ ~

Someday this world may abound in Buddhas, all its sentient beings become perfectly liberated beings, flawless in all ways, whatever the means of their becoming so. Perhaps their Wisdom and Compassion was engendered and/or engineered to Enlightenment, by biology, bionics, or Bodhicitta and the Brahma Viharas, perhaps by some combination of nature, nurture, nirvana, nano-tech, and neuro-science …

… But however that might happen, if it happens, that’s not bound to happen anytime soon.

In the meantime, while aiming for the highest peak, we can achieve much good even when just part way up the mountain. Zen teaches that every step of the path is its own place of realization.

I do not believe that we human beings need to be as flawless as an idealized, perfect Buddha in order to manifest a Buddha’s qualities throughout our lives: Being basically good and basically wise in basically most situations is already an ample touch of being basically Buddha. “Buddha” thus serves as a superlative example of good qualities and wisdom, even if we are only “Buddha-ish” much of the time, rather than Buddha-ideal all the time.

Perfection may always remain an impossible ideal. However, it is a teaching in many corners of Buddhism, such as in Soto Zen Buddhism, the tradition in which I practice, that one need not be a perfect Buddha to manifest Buddha in life. We might say that, underneath the rough surface, we all are already Buddha (or have the potential to be). When we act well and gently, we bring the Buddha to life in our lives, and make the Buddha’s enlightenment shine. Unfortunately, when we do the opposite and act with ugliness, such as with hate or greed, we hide the Buddha. We sometimes say, for example, that when we act with generosity, using our hands to offer kindness or charity, our hands become a Buddha’s hands. It is the opposite if those hands grab with greed or fill with a weapon to use in anger.

Thus, though short of being a perfect Buddha, but inspired by Buddha, we can make some important and lasting improvements to the human condition. One may say that any instant of acting like a Buddha would do is a perfect moment of doing well.

If, in the the future, inspired by Buddha, we can manage three small tweaks to the negative aspects of how we feel, react, and thus behave in life, this world will be a much nicer place. Not perfect, but much nicer.

On the other hand, should we fail to make these changes, we will witness the world’s hastening implosion by war, excess, selfishness, poverty, hunger and environmental collapse. We cannot continue on the courses we are on.

Should the technology come in time, should we have the ability to use it, should it prove safe and effective, should it be ethical to use (all big "shoulds" which must each be the case) then perhaps we can achieve a reformation of human nature through a careful and judicious use of “genetically engineered” Buddhism and “socially engaged” Buddhism, emotional moderation by neuro-mediation, Bud-dha via Bud-DNA, Zentech and Gentech, enhanced wisdom through enhanced biology, compassion called forth in the cortex, Kannon in our chromosomes, Precepts by prescription, peace pills and love lozenges, a union of meditation, mechanization, moderation and medication. Yes, we must tread with extreme caution lest our good intentions backfire. Any measures should be tested and retested before employ. However, even surprisingly minor changes in human personality would have widespread, lasting effects consistent with Buddhist values, achieving positive social goals shared by humanitarians of many creeds concerned for our survival.

What are the three negative aspects calling for adjustment?

First is excess desire, “greed” in Buddhist teachings. Greed is not the same as all desire, for ordinary desire is manageable and a necessary facet of being human, responsible for everything from our willingness to get out of bed in the morning, plant the crops, breed and feed the babies, to humanity’s great artistic creations and our having landed on the moon. The Buddha did not teach that all desires are harmful. Only excess and unhealthy desires are a problem, resulting in true addictions to food, sex, money and a thousand other things. Excess attachment and clinging to our desired goals are also a source of personal frustration and human conflict, leading to incessant discontents when the state of circumstances in life is not how we desire. Greed leads to runaway consumerism, poisoned air and water, obesity, to exploitation of other sentient beings so that we may acquire what we desire, wars wherein one group demands or grabs what it wants rather than sharing equitably the riches of this world with others.

Second, there is anger and violence, best tuned down or totally avoided. These also result from desire, when others fail to comply with our desires, to the point that we grow angry, wishing to punish or compel the others by force. It is not the small peeve or little irritation, but rage and revenge, a matter of extreme. Most people know how to live in society peacefully, avoiding degrees of fury which result in physical harm to others, such as assault and murder. Sadly, a minority do not. An angry thought is not an angry word, an angry word is not a raised fist or thrown bomb. Non-violence need not be passivity: There are times we may need violence in defense, or may feel called upon to engage in non-violent civil protest based on a sense of social outrage and injustice. However, we can avoid true anger even in acting then. It is a matter of scale, keeping the burning fires low, under control, but not out.

The third human condition in need of reconditioning is divided thinking, often called “ignorance” in Buddhist talk, manifesting in a variety of harmful ways in our lives and world. Divided thinking causes us to have a sense of being somehow separate and alienated from other people, and from the situation and conditions of our lives, feeling often as if it is “me against the world” and “me against you,” never quite at home, experiencing conflict with outside conditions.

In fact, we need divided thinking in countless varieties just to live and thrive as people, for in order to function as a person I must experience that the chair in which I sit is somehow separate from me, that the rain pouring on others’ heads does not directly make me wet, that filling your mouth with food does not fill my stomach. As with desire, the problem with divided thinking is really only a matter of excess, not the fact of categorizing, classifying, judging and distinguishing in itself, given that dividing and categorizing are the vital secret to our survival and success for millions of years, allowing us to work and compete both as individuals and as a species. A problem exists only when separation and friction, without wholeness, are the only way in which we encounter the world, or when viewpoints based on division and their accompanying tensions run to excess.

On a daily basis, most of our judgements are practical and necessary, but sometimes they reflect a chronic, disproportionate, existential dissatisfaction that leaves us perpetually restless and rarely satiated. Some degree of self-interest, as well as self-concern with our own family, is how the marketplace functions. Nonetheless, excess self-concern can result in a world of haves and have-nots. Instead of excess self-ishness, it would be good for us each to develop a heart by which, in charity, we make sure that nobody in the world is left hungry or without shelter from the rain. In Buddhist teaching, we also come to realize the ultimate truth that rain on others’ heads does make all of us wet, that your face and mouth is truly my face and mouth in other guise, for we are all merely extensions and expressions of each other.

Traditionally, in Buddhist speak, the above three tendencies of excess desire, anger/violence and divided thinking in ignorance, are known as the three poisons.

(to be continued)

Gassho, J

stlah

Comment