Never forget how special is the planet on which we live ... and it just got a little more special ...

However ...

... and on the other hand ...

... and ... possible Invaders from Mars!  ...

...

Gassho, J

stlah

The hunt for habitable planets may have just gotten far more narrow, new study finds

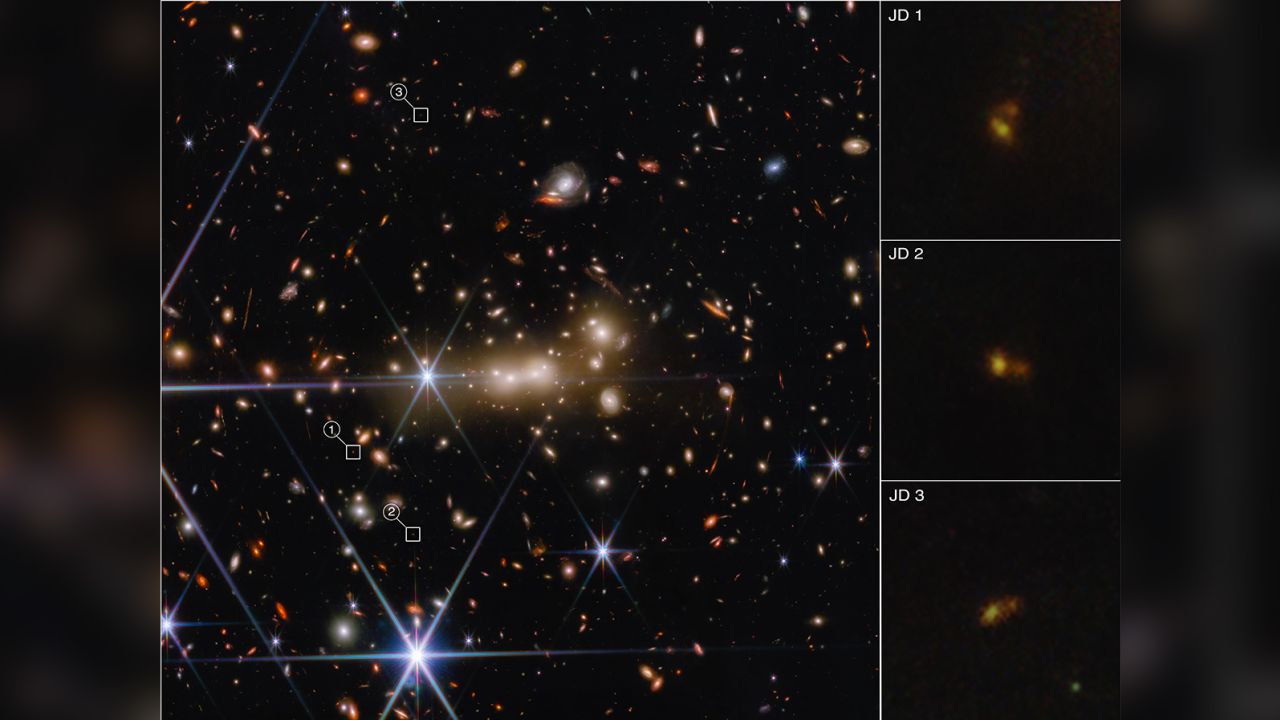

The hunt for planets that could harbor life may have just narrowed dramatically.

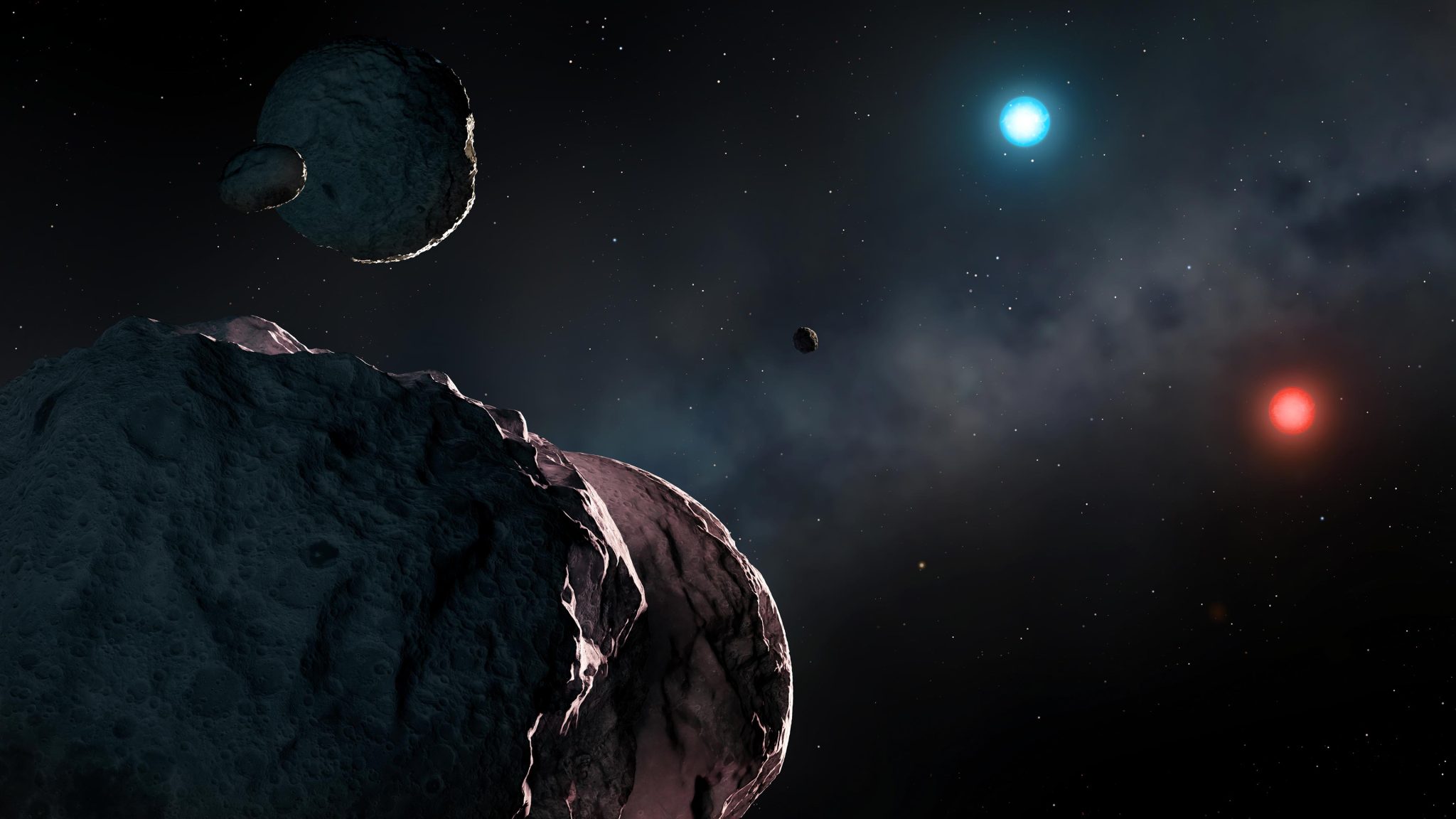

Scientists had long hoped and theorized that the most common type of star in our universe — called an M dwarf — could host nearby planets with atmospheres, potentially rich with carbon and perfect for the creation of life. But in a new study of a world orbiting an M dwarf 66 light-years from Earth, researchers found no indication such a planet could hold onto an atmosphere at all.

Without a carbon-rich atmosphere, it’s unlikely a planet would be hospitable to living things. Carbon molecules are, after all, considered the building blocks of life. And the findings don’t bode well for other types of planets orbiting M dwarfs, said study coauthor Michelle Hill, a planetary scientist and a doctoral candidate at the University of California, Riverside.

“The pressure from the star’s radiation is immense, enough to blow a planet’s atmosphere away,” Hill said in a post on the university’s website.

M dwarf stars are known to be volatile, sputtering out solar flares and raining radiation on nearby celestial bodies. But for years, the hope had been that fairly large planets orbiting near M dwarfs could be in a Goldilocks environment, close enough to their small star to keep warm and large enough to cling onto its atmosphere.

The nearby M dwarf, however, could be too intense to keep the atmosphere intact, according to the new study, which was published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

A similar phenomenon happens in our solar system: Earth’s atmosphere also deteriorates because of outbursts from its nearby star, the sun. The difference is that Earth has enough volcanic activity and other gas-emitting activity to replace the atmospheric loss and make it barely detectable, according to the research.

However, the M dwarf planet examined in the study, GJ 1252b, “could have 700 times more carbon than Earth has, and it still wouldn’t have an atmosphere. It would build up initially, but then taper off and erode away,” said study coauthor and UC Riverside astrophysicist Stephen Kane, in a news release.

GJ 1252b orbits less than a million miles from its home star, called GJ_1252. The planet reaches sweltering daytime temperatures of up to 2,242 degrees Fahrenheit (1,228 degrees Celsius), the study found.

The hunt for planets that could harbor life may have just narrowed dramatically.

Scientists had long hoped and theorized that the most common type of star in our universe — called an M dwarf — could host nearby planets with atmospheres, potentially rich with carbon and perfect for the creation of life. But in a new study of a world orbiting an M dwarf 66 light-years from Earth, researchers found no indication such a planet could hold onto an atmosphere at all.

Without a carbon-rich atmosphere, it’s unlikely a planet would be hospitable to living things. Carbon molecules are, after all, considered the building blocks of life. And the findings don’t bode well for other types of planets orbiting M dwarfs, said study coauthor Michelle Hill, a planetary scientist and a doctoral candidate at the University of California, Riverside.

“The pressure from the star’s radiation is immense, enough to blow a planet’s atmosphere away,” Hill said in a post on the university’s website.

M dwarf stars are known to be volatile, sputtering out solar flares and raining radiation on nearby celestial bodies. But for years, the hope had been that fairly large planets orbiting near M dwarfs could be in a Goldilocks environment, close enough to their small star to keep warm and large enough to cling onto its atmosphere.

The nearby M dwarf, however, could be too intense to keep the atmosphere intact, according to the new study, which was published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

A similar phenomenon happens in our solar system: Earth’s atmosphere also deteriorates because of outbursts from its nearby star, the sun. The difference is that Earth has enough volcanic activity and other gas-emitting activity to replace the atmospheric loss and make it barely detectable, according to the research.

However, the M dwarf planet examined in the study, GJ 1252b, “could have 700 times more carbon than Earth has, and it still wouldn’t have an atmosphere. It would build up initially, but then taper off and erode away,” said study coauthor and UC Riverside astrophysicist Stephen Kane, in a news release.

GJ 1252b orbits less than a million miles from its home star, called GJ_1252. The planet reaches sweltering daytime temperatures of up to 2,242 degrees Fahrenheit (1,228 degrees Celsius), the study found.

There are, however, still plenty of interesting places to hunt for habitable worlds. Apart from looking to planets farther away from M dwarfs that could be more likely to retain an atmosphere, there are still roughly 1,000 sunlike stars relatively near Earth that could have their own planets circling within habitable zones, according to the UC Riverside post about the study.

https://us.cnn.com/2022/10/25/world/...scn/index.html

https://us.cnn.com/2022/10/25/world/...scn/index.html

A new study finds the chances of uncovering life on Mars are better than previously expected.

Researchers simulated Mars’ harsh ionizing radiation conditions to see how long dried, frozen bacteria and fungi could survive.

Previous studies found ‘Conan the Bacterium’ (Deinococcus radiodurans) could survive over a million years in Mars’ harsh ionizing radiation.

A new study shatters that record, finding the hearty bacterium could survive 280 million years if buried.

This means evidence of life could still be dormant and buried below Mars’ surface.

... Because the scientists proved that certain strains of bacteria can survive despite Mars’ harsh environment, this also means that future astronauts and space tourists could inadvertently contaminate Mars with their own hitchhiking bacteria.

Researchers simulated Mars’ harsh ionizing radiation conditions to see how long dried, frozen bacteria and fungi could survive.

Previous studies found ‘Conan the Bacterium’ (Deinococcus radiodurans) could survive over a million years in Mars’ harsh ionizing radiation.

A new study shatters that record, finding the hearty bacterium could survive 280 million years if buried.

This means evidence of life could still be dormant and buried below Mars’ surface.

... Because the scientists proved that certain strains of bacteria can survive despite Mars’ harsh environment, this also means that future astronauts and space tourists could inadvertently contaminate Mars with their own hitchhiking bacteria.

...

...

“We concluded that terrestrial contamination on Mars would essentially be permanent — over timeframes of thousands of years,” said Hoffman, a senior co-author of the study. “This could complicate scientific efforts to look for Martian life. Likewise, if microbes evolved on Mars, they could be capable of surviving until present day. That means returning Mars samples could contaminate Earth.”

Gassho, J

stlah

Comment