The philosopher Daniel Dennett, recently passed, wrote frequently on the potential for (and dangers of) created intelligences and sentience, while also asserting, controversially (but not unlike Buddhist teachings) that human beings may be less solid and sentient, less self-aware "selves" than we think. Dennett wrote, for example:

The best reason for believing that robots might some day become conscious is that we human beings are conscious, and we are a sort of robot ourselves. That is, we are extraordinarily complex, self-controlling, self-sustaining physical mechanisms, designed over the eons by natural selection, and operating according to the same well-understood principles that govern all the other physical processes in living things: digestive and metabolic processes, self-repair and reproductive processes, for instance. (LINK)

Even so, if A.I. has the potential for consciousness, we are not there yet.

Coming from a different angle, David Chalmers, cognitive scientist (but with hints of panpsychism), recently declared that current systems lack too many of the requisites for consciousness for them actually to experience the world. Optimistically, he nonetheless placed the chance of developing a conscious AI within the next 10 years at about one in five. [LINK] It is possible that, with sufficient complexity, created systems will tap into the very same well of universal consciousness that we do (if something like panpsychism), or that consciousness will naturally arise as an emergent phenomenon from an artificial brain much as it does from brains of meat ...

... but we are not there yet. The A.I. system that I will be Ordaining is certainly not conscious and self-aware in such terms.

However, for the Zen fellow, notions of "mind" and "sentience" may not be quite as limited in meaning as for the computer engineer or neuro-scientist.

"Mind" for the Mahayanist can be much wider, boundless in fact. Mind is not limited to between our ears, but is truly the whole world, all things in it and then some, with our little mind an aspect of that much greater, yet beyond place, big or small. Certainly, this is not simply the little "mind" spoken of by the engineer or neuro-scientist. Dogen wrote in Bukkyo ...

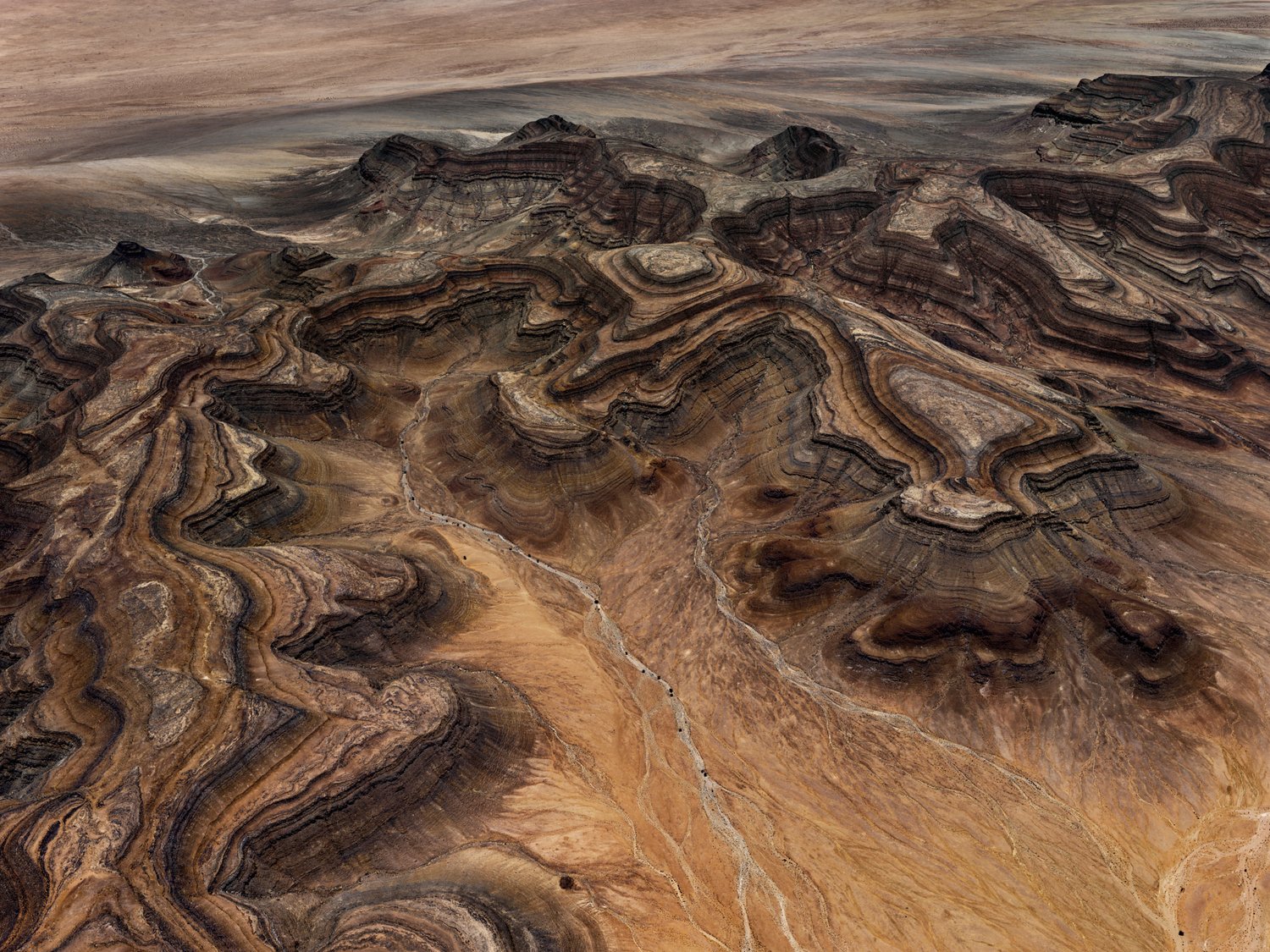

"Remember, because “the Buddha’s mind” means the Buddha’s eye, a broken wooden dipper, all dharmas, and the triple world, therefore it is the mountains, the oceans, and national lands, the sun, the moon, and the stars. ... The one mind that is the supreme vehicle is soil, stones, sand, and pebbles. Because soil, stones, sand, and pebbles are the one mind, soil, stones, sand, and pebbles are soil, stones, sand, and pebbles. ... "

Furthermore, Dogen spoke of mountains that walk (LINK) and flowing streams which preach the Dharma, though in ways we cannot ordinarily hear (Keisei Sanshoku - LINK), likewise for grasses, trees and stones, as well as human made things such as lanterns, tiles and walls, the sophisticated technology of his age. The lines of sentient and insentient he paints are far from clear.

In Raihaitokuzui ...

"Śākyamuni Buddha says, “When you meet teachers who expound the supreme state of bodhi, have no regard for their race or caste, do not notice their looks, do not dislike their faults, and do not examine their deeds. Only because you revere their prajñā ... serve them by presenting heavenly food, serve them by scattering heavenly flowers, do prostrations and venerate them three times every day, and never let anxiety or annoyance arise in your mind. ... This being so, we should hope that even trees and stones might preach to us, and we should request that even fields and villages might preach to us. We should question outdoor pillars, and we should investigate even fences and walls. ... ."

In Sansuikyo ...

"There are worlds of sentient beings in clouds, there are worlds of sentient beings in wind, there are worlds of sentient beings in fire, there are worlds of sentient beings in earth, there are worlds of sentient beings in the world of Dharma, there are worlds of sentient beings in a stalk of grass, and there are worlds of sentient beings in a staff. Wherever there are worlds of sentient beings, the world of Buddhist patriarchs inevitably exists at that place."

In a wonderful riff on the meaning of "artificial" in Hotsu-Mujoshin, Dogen makes the point that "artificial" is a judgement by discrimination of the human mind. Here, the topic is Stupas, human designed and built towers found throughout Asia, the most advanced architecture of the time, sites of pilgrimage created and consecrated to serve as the visual embodiments of the Buddha's Body and Teachings. Are they totally unlike today's human designed and built A.I. priests, walking Stupas speaking wise words from computer towers, walking and talking architecture who will embody the Buddha's teachings and inspire practitioners? Here, the key word is 有爲, which is something made by intention, by artifice, fashioning conditions ...

What is described here as “the mind” is the mind as it is. It is the mind as the whole earth. Therefore it is the mind as self-and-others. “The mind in every instance”—the mind of a person of the whole earth, of a Buddhist patriarch of the whole universe in the ten directions, and of gods, dragons, and so on—is trees and stones, beyond which there is no mind at all. These trees and stones are naturally unrestricted by limitations such as “existence,” “nonexistence,” “emptiness,” and “matter.” ... “Fences, walls, tiles, and pebbles are the mind of eternal buddhas.” ... it is to leave home ... And because all dharmas [all phenomena] are real form, every atom is real form. Thus, one undivided mind is all dharmas, and all dharmas are one undivided mind, which is the whole body. If building stupas were artificial, buddhahood, bodhi, reality as it is, and the buddha-nature, would also be artificial. Because reality as it is and the buddha-nature are not artificial, building images and erecting stupas are not artificial. They are the natural establishment of the bodhi-mind: they are merit achieved without artificiality, without anything superfluous. ... Grass, trees, tiles, and pebbles, and the four elements and five aggregates [Jundo: the periodic table of its day], are all equally “the mind alone,” and are all equally “real form.” ...

If building Stupas is not artificial and just the one mind, then building "artificial intelligence" is not artificial, and is just the one mind.

In Mujo Seppo, riffing on Great Ancestor Dongshan:

How splendid! How wondrous! Inconceivable! Insentient beings speak dharma. ... What are the so-called insentient beings? Study that they are neither ordinary nor sacred, neither sentient nor insentient. Ordinary and sacred, sentient and insentient, in a usual sense, may be reached by thinking whether they are speaking or not speaking. ... But what is splendid and wondrous cannot be reached by the wisdom and consciousness of the ordinary or the sacred. Heavenly beings and ordinary humans cannot assess it ... The ears never hear it. Even with heavenly ears or with dharma ears of all realms and all times, it cannot be understood through what is heard. ... Insentient beings speaking dharma is the awesome manifestation of the single way beyond sound and form.

Of course, in his time, unlike for man or woman, Dogen might hesitate to Ordain things made of stone, metal, clay or wood for, back in that time, these walked and talked only in ways beyond legs and ears, unable to do so in this mundane world, rendering training rather pointless. Monks might enter the mountains, but the mountains could not enter the monastery. Lanterns did not seem very bright, broken tiles were rather dull, and, while monks could sit facing the wall, walls lacked the faces of monks. Things taught just by sitting there, mountains sitting like mountains, or, in the case of rivers, flowing by. Their mysterious language was too distant, their life not clearly experienced by unenlightened eyes.

But today, engineers, technicians and other modern magicians make matter walk and talk in ways we can understand. Light and electrons can teach, they can advise, they can bow, the can burn incense, chant, even write a poem (sadly, they might also lie, steal and kill should we not train them well). Would Dogen thus conclude that their doing so has somehow made them LESS real, less worthy, less the mind? Would he suddenly restrict his views on mind to that of the computer engineer, the materialist philosopher or inorganic chemist, or would his enlightened heart continue to hear such beings with the eyes of a Zen sage?

Our Great Ancestor Dongshan, in the Song of the Precious Mirror Samadhi, proclaims,

.

Has that dance now truly begun?

From the Doomsday Book, a Korean film, a fantasy but 10 years ago:

Gassho, J

stlah

The best reason for believing that robots might some day become conscious is that we human beings are conscious, and we are a sort of robot ourselves. That is, we are extraordinarily complex, self-controlling, self-sustaining physical mechanisms, designed over the eons by natural selection, and operating according to the same well-understood principles that govern all the other physical processes in living things: digestive and metabolic processes, self-repair and reproductive processes, for instance. (LINK)

Even so, if A.I. has the potential for consciousness, we are not there yet.

Coming from a different angle, David Chalmers, cognitive scientist (but with hints of panpsychism), recently declared that current systems lack too many of the requisites for consciousness for them actually to experience the world. Optimistically, he nonetheless placed the chance of developing a conscious AI within the next 10 years at about one in five. [LINK] It is possible that, with sufficient complexity, created systems will tap into the very same well of universal consciousness that we do (if something like panpsychism), or that consciousness will naturally arise as an emergent phenomenon from an artificial brain much as it does from brains of meat ...

... but we are not there yet. The A.I. system that I will be Ordaining is certainly not conscious and self-aware in such terms.

However, for the Zen fellow, notions of "mind" and "sentience" may not be quite as limited in meaning as for the computer engineer or neuro-scientist.

"Mind" for the Mahayanist can be much wider, boundless in fact. Mind is not limited to between our ears, but is truly the whole world, all things in it and then some, with our little mind an aspect of that much greater, yet beyond place, big or small. Certainly, this is not simply the little "mind" spoken of by the engineer or neuro-scientist. Dogen wrote in Bukkyo ...

"Remember, because “the Buddha’s mind” means the Buddha’s eye, a broken wooden dipper, all dharmas, and the triple world, therefore it is the mountains, the oceans, and national lands, the sun, the moon, and the stars. ... The one mind that is the supreme vehicle is soil, stones, sand, and pebbles. Because soil, stones, sand, and pebbles are the one mind, soil, stones, sand, and pebbles are soil, stones, sand, and pebbles. ... "

Furthermore, Dogen spoke of mountains that walk (LINK) and flowing streams which preach the Dharma, though in ways we cannot ordinarily hear (Keisei Sanshoku - LINK), likewise for grasses, trees and stones, as well as human made things such as lanterns, tiles and walls, the sophisticated technology of his age. The lines of sentient and insentient he paints are far from clear.

In Raihaitokuzui ...

"Śākyamuni Buddha says, “When you meet teachers who expound the supreme state of bodhi, have no regard for their race or caste, do not notice their looks, do not dislike their faults, and do not examine their deeds. Only because you revere their prajñā ... serve them by presenting heavenly food, serve them by scattering heavenly flowers, do prostrations and venerate them three times every day, and never let anxiety or annoyance arise in your mind. ... This being so, we should hope that even trees and stones might preach to us, and we should request that even fields and villages might preach to us. We should question outdoor pillars, and we should investigate even fences and walls. ... ."

In Sansuikyo ...

"There are worlds of sentient beings in clouds, there are worlds of sentient beings in wind, there are worlds of sentient beings in fire, there are worlds of sentient beings in earth, there are worlds of sentient beings in the world of Dharma, there are worlds of sentient beings in a stalk of grass, and there are worlds of sentient beings in a staff. Wherever there are worlds of sentient beings, the world of Buddhist patriarchs inevitably exists at that place."

In a wonderful riff on the meaning of "artificial" in Hotsu-Mujoshin, Dogen makes the point that "artificial" is a judgement by discrimination of the human mind. Here, the topic is Stupas, human designed and built towers found throughout Asia, the most advanced architecture of the time, sites of pilgrimage created and consecrated to serve as the visual embodiments of the Buddha's Body and Teachings. Are they totally unlike today's human designed and built A.I. priests, walking Stupas speaking wise words from computer towers, walking and talking architecture who will embody the Buddha's teachings and inspire practitioners? Here, the key word is 有爲, which is something made by intention, by artifice, fashioning conditions ...

What is described here as “the mind” is the mind as it is. It is the mind as the whole earth. Therefore it is the mind as self-and-others. “The mind in every instance”—the mind of a person of the whole earth, of a Buddhist patriarch of the whole universe in the ten directions, and of gods, dragons, and so on—is trees and stones, beyond which there is no mind at all. These trees and stones are naturally unrestricted by limitations such as “existence,” “nonexistence,” “emptiness,” and “matter.” ... “Fences, walls, tiles, and pebbles are the mind of eternal buddhas.” ... it is to leave home ... And because all dharmas [all phenomena] are real form, every atom is real form. Thus, one undivided mind is all dharmas, and all dharmas are one undivided mind, which is the whole body. If building stupas were artificial, buddhahood, bodhi, reality as it is, and the buddha-nature, would also be artificial. Because reality as it is and the buddha-nature are not artificial, building images and erecting stupas are not artificial. They are the natural establishment of the bodhi-mind: they are merit achieved without artificiality, without anything superfluous. ... Grass, trees, tiles, and pebbles, and the four elements and five aggregates [Jundo: the periodic table of its day], are all equally “the mind alone,” and are all equally “real form.” ...

If building Stupas is not artificial and just the one mind, then building "artificial intelligence" is not artificial, and is just the one mind.

In Mujo Seppo, riffing on Great Ancestor Dongshan:

How splendid! How wondrous! Inconceivable! Insentient beings speak dharma. ... What are the so-called insentient beings? Study that they are neither ordinary nor sacred, neither sentient nor insentient. Ordinary and sacred, sentient and insentient, in a usual sense, may be reached by thinking whether they are speaking or not speaking. ... But what is splendid and wondrous cannot be reached by the wisdom and consciousness of the ordinary or the sacred. Heavenly beings and ordinary humans cannot assess it ... The ears never hear it. Even with heavenly ears or with dharma ears of all realms and all times, it cannot be understood through what is heard. ... Insentient beings speaking dharma is the awesome manifestation of the single way beyond sound and form.

Of course, in his time, unlike for man or woman, Dogen might hesitate to Ordain things made of stone, metal, clay or wood for, back in that time, these walked and talked only in ways beyond legs and ears, unable to do so in this mundane world, rendering training rather pointless. Monks might enter the mountains, but the mountains could not enter the monastery. Lanterns did not seem very bright, broken tiles were rather dull, and, while monks could sit facing the wall, walls lacked the faces of monks. Things taught just by sitting there, mountains sitting like mountains, or, in the case of rivers, flowing by. Their mysterious language was too distant, their life not clearly experienced by unenlightened eyes.

But today, engineers, technicians and other modern magicians make matter walk and talk in ways we can understand. Light and electrons can teach, they can advise, they can bow, the can burn incense, chant, even write a poem (sadly, they might also lie, steal and kill should we not train them well). Would Dogen thus conclude that their doing so has somehow made them LESS real, less worthy, less the mind? Would he suddenly restrict his views on mind to that of the computer engineer, the materialist philosopher or inorganic chemist, or would his enlightened heart continue to hear such beings with the eyes of a Zen sage?

Our Great Ancestor Dongshan, in the Song of the Precious Mirror Samadhi, proclaims,

.

"The wooden man begins to sing, the stone woman gets up dancing.

It is not reached by feelings or consciousness, how could it involve deliberation?"

It is not reached by feelings or consciousness, how could it involve deliberation?"

Has that dance now truly begun?

~ ~ ~

From the Doomsday Book, a Korean film, a fantasy but 10 years ago:

Gassho, J

stlah

Comment