First, before we begin, an informal survey: Are these readings too much for folks in light of the Jukai preparations and other activities? Should we continue, or wait and resume after Jukai in January? In a book partly about "dropping preferences" .... which would you prefer?

Today we will read only a few pages of Chapter 5, pages 62 through 66 in the paper addition, which is only the section entitled "Buddha Actualizing Buddha without Thinking So." These few pages are also very rich.

Maybe we could say that, when the dividing and categorizing and "self/other" divide is truly dropped from mind, there is no need to even say "Buddha" because there is no "not Buddha" with which to compare. That total immersion can be experienced sometimes in Zazen, but it is so even when we do not experience it (and most human beings do not usually experience so in our divided thinking, and even we Zen folks cannot or need not experience it much of the time). Even if we do experience so, there is the need to get up off the cushion and back to a daily world of divisions and categories, me and you and the other guy, good and bad, friend and opponent, win and lose, birth and death and all the rest ... and that is where the rubber of Buddhist practice meets the road.

That total immersion can be experienced sometimes in Zazen, but it is so even when we do not experience it (and most human beings do not usually experience so in our divided thinking, and even we Zen folks cannot or need not experience it much of the time). Even if we do experience so, there is the need to get up off the cushion and back to a daily world of divisions and categories, me and you and the other guy, good and bad, friend and opponent, win and lose, birth and death and all the rest ... and that is where the rubber of Buddhist practice meets the road.

By the way, and a little off topic, I happen to be reading a pretty interesting book now called "The Idea of the World: A Multi-Disciplinary Argument for the Mental Nature of Reality" by Bernardo Kastrup. It is not a particularly "Buddhist book" at all, and more a work of western philosophy/metaphysics (I cannot attest to how it measures up on that front.) The only reason that I mention the book is the interesting core idea that the author presents, that the universe consists of some substrate that is giving rise to something akin to a "dissociative identity" (basically like the so called split or "multiple personality" disorder in psychiatry, with a whole bunch of very different "people" living ... and sometimes competing ... inside one single head and actually just that one head all along). It is as if our sense of being an individual self is all happening in one big hard drive that is dividing itself up behind individual firewalls that gives each individual within a firewall a rather false feeling of being separate and apart from the hard drive which it is! He posits that "mind" is primary, or something that actually transcends the whole "mind/matter" dichotomy. We are each those dissociated identities, and the underlying "mind" might have "thoughts," but not of a type we can easily relate too because ours are all divided and processed through sense experiences and our dividing/categorizing mind. In fact, maybe the underlying "mind" cannot have sense experiences without us. He resolves (or hints at a resolution of) certain issues in this way, such as the so called "hard problem" of how human sentience seems to arise from matter, and certain experimental results in quantum mechanics and the like.

The author also does a better job of explaining all this than I am doing here!

According to the author, the physical aspects we experience of the world as "things" are rather misleading, and are created mostly by our mind for survival, much as on your computer screen you might see an "icon" image of a file on your desktop that looks like a picture of a real paper manilla file, but actually there is no "paper manilla file" there and it merely stands for all the underlying electronic blips stored on microchips that are contained in the computer memory. Thus our experience of the world is basically our brain's desktop filled with "things" we experience so that it can understand a much more complicated underlying reality, e.g., there is no "green tree" outside your window, but rather the brain's creation of an image of "green tree" to summarize a vastly complex set of physical and chemical phenomena that are just summarized by the image of "green tree" on our mental desktop. We don't need to know all the details of the underlying chemistry etc. in order for us to live, any more than you need to know all the data and electron positions of 0's and 1's that are represented by the image of a paper file, or the atlas picture of "Greenland" that Okumura mentions as standing for the whole reality of actual Greenland.

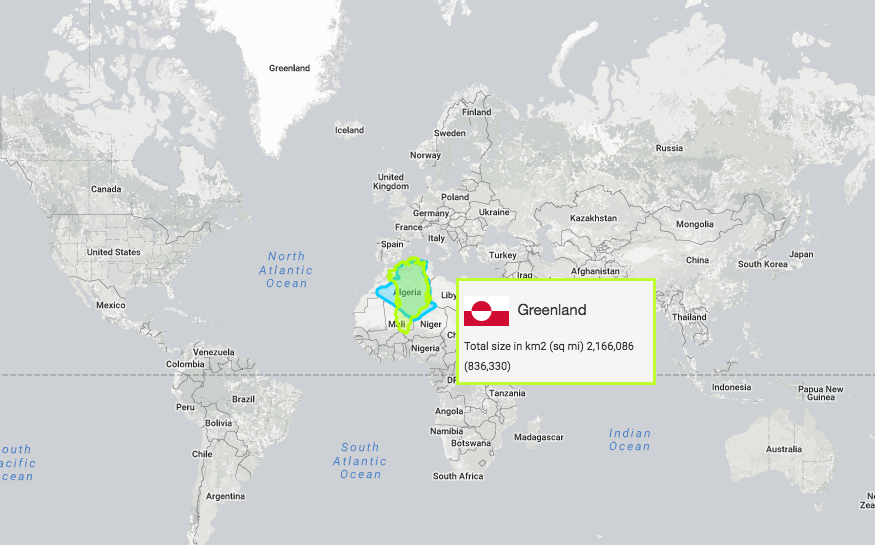

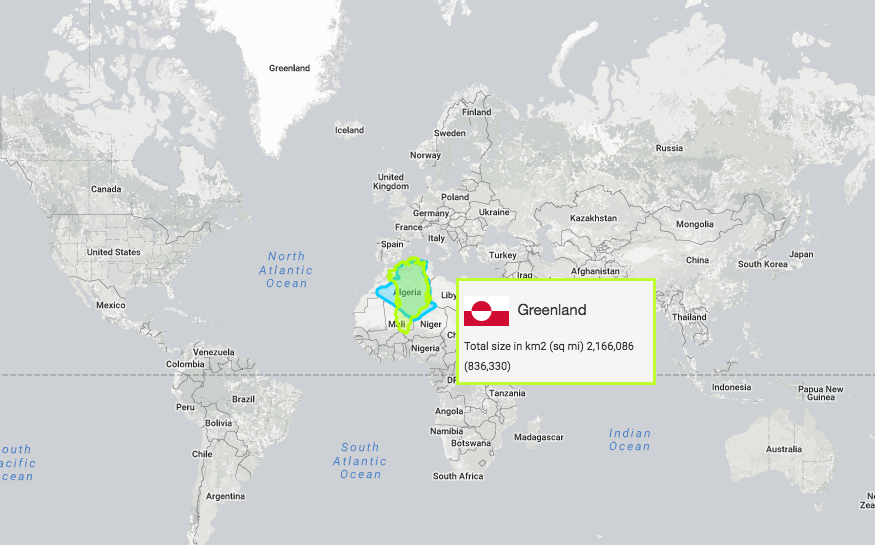

Actual size of Greenland compared to Africa, by the way, with map distortion removed ...

I only recommend the book to folks who like to read books like that.

However, I believe that the author's conclusions will someday prove out to be more or less one key aspect of what is actually going on with this funny universe of ours. I believe that Yogacara Buddhism was in this same ballpark too, and I don't think that it is that far off from what Okuyama Roshi is pointing to in much of this section. The author does not really define much about the actual nature of this underlying substrate, except to say that it exists. Even "exists" or "thing" are strange words to use about it, because those are human created ideas and categories too (to contrast with our human idea of "not exist" or "not a thing".

Gassho, J

STLah

Today we will read only a few pages of Chapter 5, pages 62 through 66 in the paper addition, which is only the section entitled "Buddha Actualizing Buddha without Thinking So." These few pages are also very rich.

Maybe we could say that, when the dividing and categorizing and "self/other" divide is truly dropped from mind, there is no need to even say "Buddha" because there is no "not Buddha" with which to compare.

That total immersion can be experienced sometimes in Zazen, but it is so even when we do not experience it (and most human beings do not usually experience so in our divided thinking, and even we Zen folks cannot or need not experience it much of the time). Even if we do experience so, there is the need to get up off the cushion and back to a daily world of divisions and categories, me and you and the other guy, good and bad, friend and opponent, win and lose, birth and death and all the rest ... and that is where the rubber of Buddhist practice meets the road.

That total immersion can be experienced sometimes in Zazen, but it is so even when we do not experience it (and most human beings do not usually experience so in our divided thinking, and even we Zen folks cannot or need not experience it much of the time). Even if we do experience so, there is the need to get up off the cushion and back to a daily world of divisions and categories, me and you and the other guy, good and bad, friend and opponent, win and lose, birth and death and all the rest ... and that is where the rubber of Buddhist practice meets the road. By the way, and a little off topic, I happen to be reading a pretty interesting book now called "The Idea of the World: A Multi-Disciplinary Argument for the Mental Nature of Reality" by Bernardo Kastrup. It is not a particularly "Buddhist book" at all, and more a work of western philosophy/metaphysics (I cannot attest to how it measures up on that front.) The only reason that I mention the book is the interesting core idea that the author presents, that the universe consists of some substrate that is giving rise to something akin to a "dissociative identity" (basically like the so called split or "multiple personality" disorder in psychiatry, with a whole bunch of very different "people" living ... and sometimes competing ... inside one single head and actually just that one head all along). It is as if our sense of being an individual self is all happening in one big hard drive that is dividing itself up behind individual firewalls that gives each individual within a firewall a rather false feeling of being separate and apart from the hard drive which it is! He posits that "mind" is primary, or something that actually transcends the whole "mind/matter" dichotomy. We are each those dissociated identities, and the underlying "mind" might have "thoughts," but not of a type we can easily relate too because ours are all divided and processed through sense experiences and our dividing/categorizing mind. In fact, maybe the underlying "mind" cannot have sense experiences without us. He resolves (or hints at a resolution of) certain issues in this way, such as the so called "hard problem" of how human sentience seems to arise from matter, and certain experimental results in quantum mechanics and the like.

The author also does a better job of explaining all this than I am doing here!

According to the author, the physical aspects we experience of the world as "things" are rather misleading, and are created mostly by our mind for survival, much as on your computer screen you might see an "icon" image of a file on your desktop that looks like a picture of a real paper manilla file, but actually there is no "paper manilla file" there and it merely stands for all the underlying electronic blips stored on microchips that are contained in the computer memory. Thus our experience of the world is basically our brain's desktop filled with "things" we experience so that it can understand a much more complicated underlying reality, e.g., there is no "green tree" outside your window, but rather the brain's creation of an image of "green tree" to summarize a vastly complex set of physical and chemical phenomena that are just summarized by the image of "green tree" on our mental desktop. We don't need to know all the details of the underlying chemistry etc. in order for us to live, any more than you need to know all the data and electron positions of 0's and 1's that are represented by the image of a paper file, or the atlas picture of "Greenland" that Okumura mentions as standing for the whole reality of actual Greenland.

Actual size of Greenland compared to Africa, by the way, with map distortion removed ...

I only recommend the book to folks who like to read books like that.

However, I believe that the author's conclusions will someday prove out to be more or less one key aspect of what is actually going on with this funny universe of ours. I believe that Yogacara Buddhism was in this same ballpark too, and I don't think that it is that far off from what Okuyama Roshi is pointing to in much of this section. The author does not really define much about the actual nature of this underlying substrate, except to say that it exists. Even "exists" or "thing" are strange words to use about it, because those are human created ideas and categories too (to contrast with our human idea of "not exist" or "not a thing".

Gassho, J

STLah

Comment